This catalogue surveys Beagles & Ramsay’s work made since 1996 and was published by Gasworks on the occasion of the solo show ‘Dead Of Night’ curated by Fiona Boundy.

Essays by Moira Jeffrey & Francis McKee.

Design by Giant Arc. 60 pages ISBN 0-9538059-5-6 Edition of 1000

The catalogue was also launched separately at the Collective Gallery, Edinburgh to mark the opening of the second ‘Dead Of Night’ solo show 21 June – 27 July, 2003, curated by Sarah Munro.

https://gasworks.org.uk/exhibitions/dead-of-night/

Dead Again: The Work of Beagles & Ramsay

Moira Jeffrey

Catalogue essay for Beagles and Ramsay 1996 – 2003 published by Gasworks Gallery, London.

Beagles and Ramsay’s first solo show in Scotland was posthumous. The artists attended Goodnight, Goodnight, at Edinburgh’s Collective Gallery in 1997, lying in state in a fetching double coffin. In 1999 their severed heads could be glimpsed rotting in the murky depths of the lair of an infant serial killer in Head Lung Dead, a show at the Glasgow Project Room. By August 2002 they were dead again, when a press release announced the shocking news that they were brutally murdered on the eve of a major retrospective at the Hogslande Kunstverein in Hogsberg, Germany. If the myth of making art is described in all the best biopics as a means of achieving immortality – the transcendence of the artwork finally overcoming the daily humiliation and mortification of the flesh – Beagles and Ramsay’s art condemns them, in their myriad double self-portraits, to repeated and perpetual indignity. The evil twins, duplicates, dolls, doubles and doppelgangers – bearing the distinctive faces of the artists themselves – that rampage or slump through their oeuvre (the dominant modes of activity in this work tend to fall into one of two categories: complete inaction or hysterical overreaction) find that death is never a complete release. They repeatedly rise again to suffer the regular affronts of senility, tooth decay, impotence, flatulence, bad skin, inferior diet, and daytime television.

The anxieties, both cultural and social, that run through the work of Beagles and Ramsay read like a contemporary chronology of perceived malaise. Early work featured the notorious Scottish diet, food scares including e-coli and BSE, child criminality and neighbours from hell. More recently, their interest is in narratives that describe broader but equally anxious phenomena: political disenfranchisement, the culture of consumerism, and the cult of celebrity. Across their body of work, a satirical recitation of urban myths and media scares rubs alongside deeper fears and genuine threats. The perils of consumption are a recurring theme – threats of contamination, food poisoning and infection are all-pervasive – and the persistent risk of external threat and unexpected or violent death hangs over the artists’ many representations of the disintegration and degradation of the body.

Beagles and Ramsay have worked in A4 poster format, installation, photography, video, music, critical writing and short stories – and often a conflation of all these. Increasingly their emphasis is on elaborate theatrical settings and their methods of working akin to low budget movie production. In a context where we’re schooled to expect the distinctive voice of the artist, they have chosen to speak in a whole range of tongues – from the satanic to the pathetic. Their early video narratives – in a number of genres, from pop promo, to contemporary art video and public information film – featured a cast of often recurring characters: Gary the Misunderstood Toddler, an uncontrollable child criminal; John Saxon, a kind of British everyman and inadequate John Bull clad in a parka and the Old Men, a projection of the artists themselves in lonely and repulsive old age. Most of their work involves, at some level, a satire of the current conventions around the production and display of art. Issues of sponsorship and product placement featured in early shows like Goodnight, Goodnight and at the !st Floor Gallery, Melbourne, in 1997, when the artists reflected the growing corporate presence in the gallery by liberally sprinkling their installations with silver plastic shopping bags bearing the logo of LiDL, the no frills German supermarket chain; Andy Warhol’s Silver Clouds reworked for cut-price capitalism.

Invited, in 1999, to take part in Evolution Isn’t Over Yet, at Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket Gallery one of a series of ‘new generation’ shows, worshipping at the altar of youth, the artists adopted their Old Men personas. In an art world afflicted by neophilia, their installation featured life-size effigies of the artists in bed aged, their latex-crafted faces pockmarked and flaky their pyjamas slightly soiled. In an accompanying video, Trilogy, the Old Men are shown in their miserable flat. Slouching on the sofa, snoozing in their double bed, on the loo and taking a bath, they pass down the folk wisdom they have gathered in their long lives. Their profound words turn out to be the banal lyrics of the songs Borderline, U Got the Look and Express Yourself. The Old Men, it turns out have, learnt little, their minds are addled and worn by years of exposure to pop music and there’s a yawning gap between the sexy, youthful lyrics and their own deteriorated state of body and mind.

Dub’L InTROOder, the artists’ curatorial project at Glasgow’s Transmission Gallery in 2001 featured work by artist groupings including Bank, Muntean and Rosenblum and the Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley video collaboration Heidi. Beagles and Ramsay’s own work for the show took the form of a ‘light industrial unit’, an impressively shiny aluminium structure, placed in the centre of gallery and fronted with a corporate portrait of the artists as directors of their companies New Heads on the Block and Rope a Dope productions. Inside, the artists portrayed themselves as mechanised labour. These portraits as Half Life Size Drone Workers, were surrounded by their industrial output, a range of children’s toys echoing Scotland’s self-lacerating image, including Hamish the Hooligan (commemorating the Scottish football fans who tore up the Wembley turf in 1977) and Burger Babe (the body of a children’s doll, with the head of hamburger).

This interest in modes of artistic production culminates in the Burgerheaven project in Eindhoven (2001) and Toronto (2002) where the artists set themselves up as a fast food outlet, using the commercial structure of the franchise, and familiar marketing tools such as public leafleting, promotional T-shirts, corporate colours and design. Their work often includes pastiches of other art works, The Wilson Twins, for example, in the video The Shutters are Down or Marc Quinn, in the case of the, as yet unrealised, proposal to manufacture and sell black pudding using their own blood. But the idea of critical distance often collapses in the work of Beagles and Ramsay. They inhabit the same messy and compromised world that they portray. They are angry, puerile and spiteful as often as they are funny. They are vulnerable, weak and complicit. They are embarrassed and embarrassing.

Spend any time with their work and their genuine love of comedy, horror movies, dance music, and television is also apparent. In an art world that often takes an anthropological interest in ‘real life’ and ‘pop culture’, Beagles and Ramsay are enthusiasts, shaped and smitten by the world they inhabit.

They are also inveterate and strategic liars, largely as a matter of pragmatism. When they were unable to obtain work by art duo Bob and Bob for Dub’L InTROOder they simply faked it. For Museum Magogo, a gargantuan gallery project in Glasgow and Melbourne where they invited local and international artists to contribute works to a show which was constructed as a pastiche of the conventions of the art museum, the genuine works were alternated by fakes attributed to artists including Martin Kippenberger, Lawrence Weiner, Sarah Lucas and Tracey Emin. Some of their work in virtually undetectable: their jokes, minor hoaxes and japes, the spurious or impossible proposals to galleries or funding bodies. But they lavish huge care and minute attention on their material productions including model-making, intricate sets, music and songs and elaborate written materials. Beagles and Ramsay are most frequently seen in the tradition of great British comedy duos like Morecambe and Wise, Reeves and Mortimer and Derek and Clive. But their work also evokes the more ancient and irrational humour of carnival. Death stalks their work, often in his contemporary guise of the serial killer – even the art magazine they edit Uncle Chop Chop is named after a notorious murderer. Their ambivalence about their bodies and their emphasis on the frailties of the flesh is matched by a derision that reflects an interest in the long tradition of dark philosophical and political satire in work by Rabelais, Swift, Stern and the restoration poetJohn Wilmot, Earl of Rochester. Like those writers, the artists’ parade of grotesques, their invocation of death and their bodily humour often has explicit political targets that are overlooked amongst the jokes. Burgerheaven, as well as a parody of contemporary production, is a reworking of Swift’s pamphlet A Modest Proposal in which he suggested solving famine in Ireland by eating children.

Beagles and Ramsay propose we can resolve our appetite for intimacy with dead celebrities by chewing their flesh.

Their most explicit work on the subject of political alienation, made for the ICA’s Crash, is the video We Are The People Suck On This, in which Graham Ramsay takes on the Robert De Niro role in Taxi Driver. A mild-mannered Travis Bickle, we see him pill-popping and grimacing round the streets of Whitehall and Westminster eventually handing in the artist’s hopeless petition to Tony Blair at 10 Downing Street, only to be gently led away by the police. It’s a piece in which the coruscating images of the original film – New York as a nauseating emporium in which everything is for sale – are translated into contemporary British terms. In one brief moment Ramsay stops in front of a bright façade, a shop front bearing the slogan Easy Everything. The grand streets of establishment London exemplify of a kind of resigned consensus in which political institutions are essentially moribund and pessimistic, replaced by flag-waving symbolism and rampant consumerism.

But themes of disenfranchisement and powerlessness permeate all of their work. Their self portraits as Budget Range Sex Dolls, ‘complete with prescription spectacles, heart shaped pubes and grip friendly hair’ are the embodiment of ineffectual impotence: the artists rendered as weak, pink and flaccid playthings. The video Geezer Gotta Flamethrower is as much a portrait of the artists as inadequate parents of their own terrifying creation, the toddler Gary, as it is a satire of child crime.

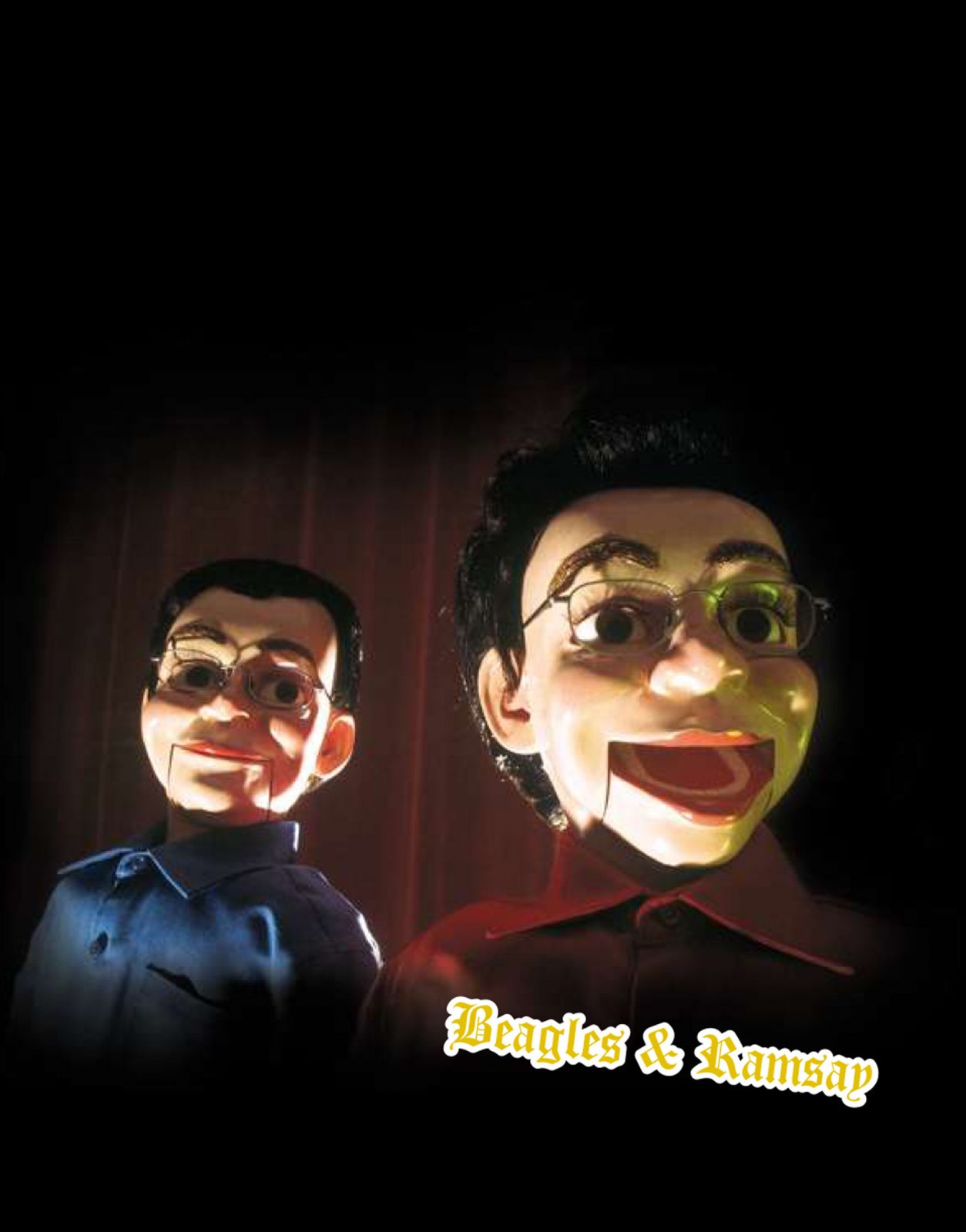

In this exhibition, Dead of Night, named after the Ealing portmanteau chiller, the artists appear as ventriloquists dummies: a reflection of their interests in voicelessness and apathy and their unabashed pleasure in theatrical set pieces. In that film the evil dummy with a life of its own is brutally smashed by its owner, the hapless and fearful ventriloquist played by Michael Redgrave, only to survive by taking possession of his soul. Likewise Beagles and Ramsay are likely to die again and rise again many more times in the course of their art.